Pride Isn't Dead

Memory and Love as Acts of Resistance

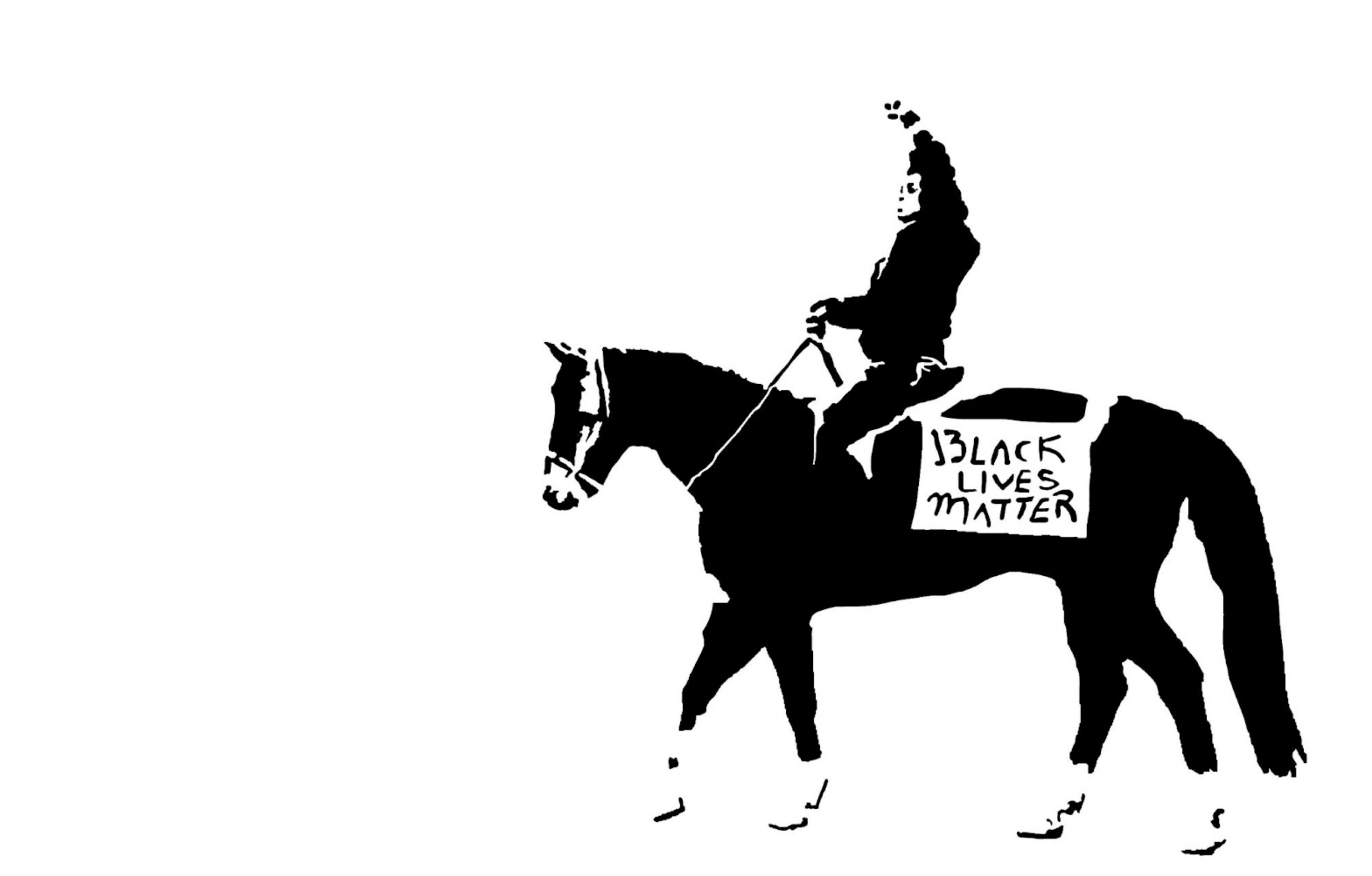

Images by Yosephina and Michaela PetersFounder of Mulatto Meadows, Brianna Noble, Protesting on Her Horse, Dapper Dan, Michaela Peters, 2020

It’s been a hard year. The start of 2025 was filled with what seemed like disaster after disaster. As Californians, we were grieving the loss of two cultural ecosystems in the LA Wildfires — entire neighborhoods of Altadena and the Palisades gone. It felt like everyone I knew either lost something or knew someone who had. And while people showed up — neighbors, strangers, whole communities coming out of the woodwork to help — nothing about it felt whole. Nothing really felt stable anymore.

We were still holding out hope for the lasting desire to keep democracy within our nation on the right track. Faith that the upcoming transition of power could be smooth and non-confrontational. At the same time, we were watching genocide unfold across the world — Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan. No corner of the globe felt untouched by violence. And the U.S.? At the center of it all, still offering to be a beacon of freedom. I didn’t feel great about where the world was turning and where we’d landed.

Since Trump returned to office, things have felt even more tense. He yelled at President Zelensky, a leader currently defending his country in war. The headlines say the economy is booming, then collapsing, then booming again. But my friends and family are still worried about rent. I’m still standing in Rite Aid, wondering why my mouthwash costs sixteen dollars

To be honest, I felt dejected. Angry. Helpless. Stuck watching the news, yelling at the screen, not because I didn’t understand what was happening, but because I did. Because deep down, I’ve always known: America has always been like this.

People say, “The end times are near,” “The world is ending.” But when isn’t it?

When protests erupted at Columbia and across campuses against Israel’s assault on Gaza, people drew connections to Berkeley in 1968 — to that same spirit of student resistance, of standing up when it feels like the world is burning. And I thought to myself… did they feel like this too? Did they feel powerless and brave at the same time? Did they wonder if it was enough?

In that moment, in the chaos and numbness and rage, I turned to Black feminist writers. Angela Davis. bell hooks. Audre Lorde. I needed my sisters. I needed clarity. I needed something to hold onto.

Because I still believe things can change. And if pride means anything to me, it has to begin with that belief — that resistance, even now, is still possible.

Sojourner Truth, Michaela Peters, 2021

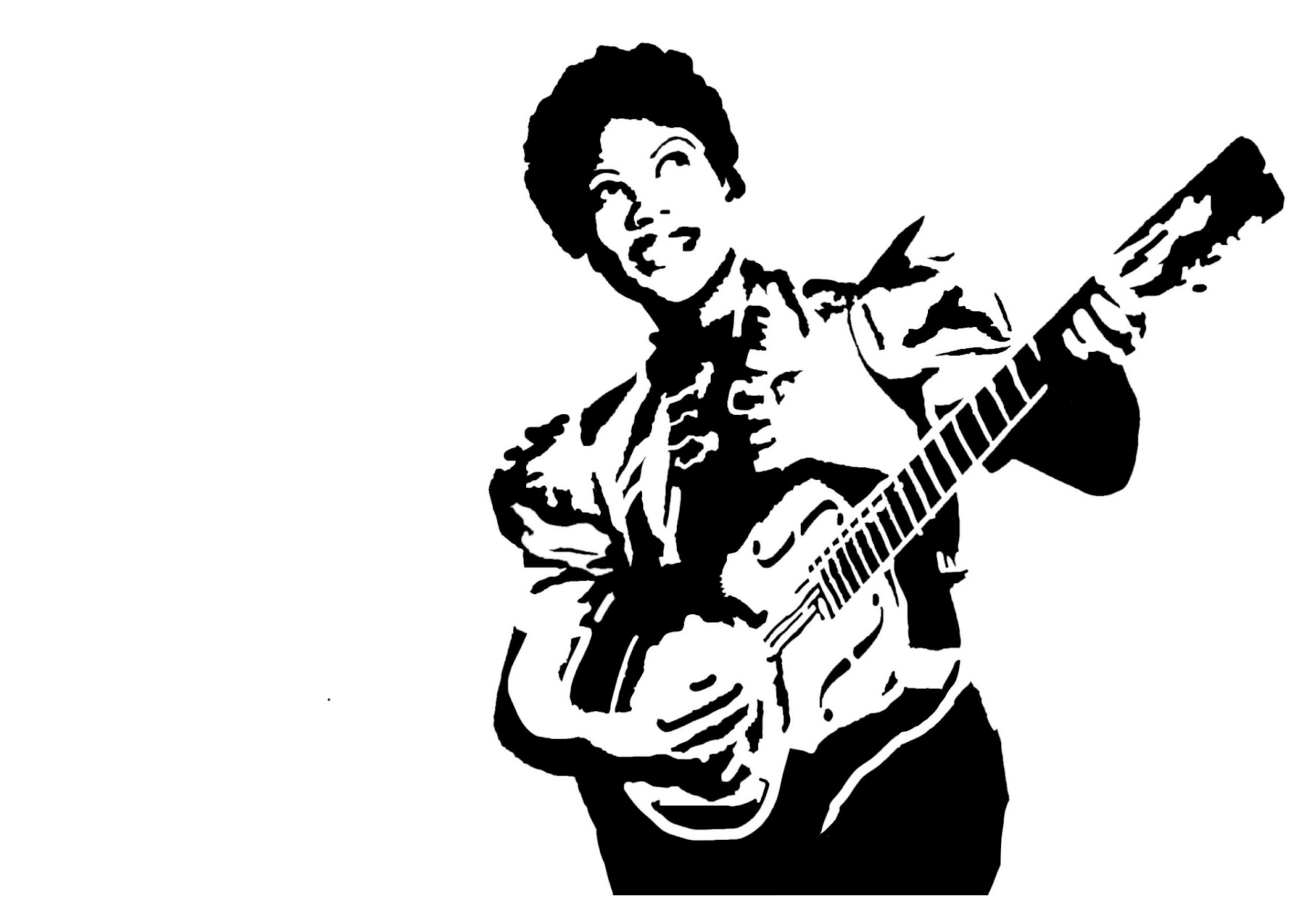

Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the “Godmother of Rock n’ Roll,” Michaela Peters, 2020

In my readings, I looked back to The 1619 Project, the groundbreaking work by Nikole Hannah-Jones published in 2019 that reframes 400 years of American history through the lens of Black enslavement and its enduring legacy. One story in particular stayed with me — a memory she shares about her father:

“My dad always flew an American flag in our front yard. The blue paint on our two-story house was perennially chipping; the fence, or the rail by the stairs, or the front door, existed in a perpetual state of disrepair, but that flag always flew pristine… When I was young, that flag outside our home never made sense to me. How could this Black man, having seen firsthand the way his country abused Black Americans, how it refused to treat us as full citizens, proudly fly its banner? I didn’t understand his patriotism. It deeply embarrassed me… Like most young people, I thought I understood so much when, in fact, I understood so little. My father knew exactly what he was doing when he raised that flag. He knew that our people’s contributions to building the richest and most powerful nation in the world were indelible — that the United States simply would not exist without us.”

That story resonated deeply with me. I was that young person — I am that young person — believing I knew everything, wondering how anyone could take pride in a country that continues to harm and erase the very people who built it. And yet, I understand what her father flew that flag for. It wasn’t blind loyalty. It was rooted in recognition — in the truth that Black, Indigenous, and immigrant people shaped this country from the ground up, and that their labor, brilliance, and resistance allowed this country to thrive.

That kind of pride is about claiming our place in the narrative — refusing to be forgotten. It’s a quiet defiance. And in that, I found a glimmer of peace. Maybe — just maybe — this nation can become what it has always promised to be.

I used to think American pride meant fireworks on the Fourth of July, flags waving on porches, and reciting the Pledge of Allegiance in school. But it’s deeper than that. For me, any understanding of American pride has to begin with the Indigenous peoples who fought — and continue to fight — for their land, their sovereignty, and their sacred relationship to what they call Turtle Island.

The term “Indigenous” came into broader use during the liberation movements of the 1960s and 70s, as marginalized groups across the world reclaimed their histories and identities. But Indigenous nations have always been here — diverse, sovereign, and deeply connected to the lands they inhabit. In California alone, there are over 500 tribal communities. Growing up in the Bay Area, I learned the histories of the Ohlone, Pomo, Wappo, and Coastal Miwok. Now living in Ojai, I reside on Chumash land — a nation whose cultural and spiritual practices have sustained them for thousands of years despite colonization, violence, and displacement.

One of the core values in Indigenous politics is reciprocity — the understanding that “knowledge emerges from reciprocal relationships” between people, land, water, and all that lives on our land. As Potawatomi scholar Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in Braiding Sweetgrass,

“All flourishing is mutual.”

This idea isn’t a metaphor. It is a lived ethic, passed down through stories, ceremony, and practice. Pride, then, isn’t performative — it’s participatory.

This Indigenous understanding of place — as home, not property — stands in stark contrast to the settler colonial logic that sees land as a resource to be extracted, sold, and claimed. And yet, despite centuries of genocide and cultural erasure, Indigenous pride endures. It lives in language revitalization programs, in land back movements, in climate organizing that defends water, mountains, and earth.

Understanding this history and acknowledging the Indigenous nations whose land we stand on is the starting place for any meaningful pride in the land we call “America.” Because without that — without Turtle Island — there is no United States. And without Indigenous resistance, we wouldn’t even have the possibility of imagining a different kind of future.

Black Lives Matter, YOSEPHINA PETERS, 2020

Bird of Palestine, Peters, 2024

There is a kind of American pride that exists quietly — unshaken, rarely interrogated, and often passed down generationally. It emerges in school assemblies with the Pledge of Allegiance, in military homecoming videos, and in the Fourth of July barbecues that overlook the violence that shaped this nation’s birth. This form of pride, deeply embedded in mainstream American identity, tends to accept the nation’s founding ideals at face value: liberty, democracy, equality. But beneath those ideals lies a more complicated foundation.

The United States was established through settler colonialism — a process not simply of migration, but of land seizure, displacement, and genocide. As scholar Patrick Wolfe writes, “settler colonialism is a structure, not an event.” This means it didn’t end with the founding; it continues to shape how the state functions, who it protects, and who it erases.

While many Americans look to the Constitution as evidence of democratic values, historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz reminds us that the document was built to serve the interests of land-owning white men, embedding within it exclusions that normalized slavery, Indigenous dispossession, and gendered disenfranchisement. The framework of liberty existed — but only for some.

This national pride is also deeply tied to the military, both as institution and symbol. Scholar Barbara Ehrenreich has described how militarism offers Americans, particularly white men, a sense of identity and belonging, framing service and war as acts of noble sacrifice. Yet for others, particularly those whose communities have borne the cost of these wars, such pride is complicated by grief, silence, and skepticism.

To be proud of America, in the dominant sense, often requires bypassing that confrontation. It asks for love without accountability, loyalty without interrogation.

Pride is a form rooted not in the state, but in self-definition. A pride that resists victimhood without erasing struggle — one that sharpens, prepares, dreams.

Perhaps it is not pride that is the problem, but the kind of pride we center. A pride that refuses complexity may offer comfort, but it cannot guide us toward justice. To love this country honestly — if one chooses to — must mean loving it enough to reckon with its origins, its contradictions, and the ongoing harm it must still undo.

A lot of my self-love — and my sense of pride — began with Black feminist authors. At The Thacher School, I didn’t always feel that pride. I worried about my class status. About the way my hair didn’t fall past my shoulders like the other girls. About whether I was “too much” — too opinionated, too honest, too resistant in classrooms where I was expected to just absorb and agree.

But that self-doubt wasn’t just mine. As Angela Davis reminds us, “We are produced by history.” The feelings I carried were part of a longer inheritance — one shaped by exclusion, assimilation, and a society that often teaches Black girls to make themselves smaller. Reading Davis helped me realize that pride isn’t arrogant. It’s corrective. It’s necessary.

She once said, “I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.” That became a turning point for me. It wasn’t dumb to push back — it was inherent.

Leading the Black Student Union gave me the space to name that feeling. I began to understand that being who I am, fully, wasn’t just a right. It was a responsibility. That pride in myself could become a mirror, helping others see their own worth, whether they were white, Black, queer, trans, rich or poor. With love, we could break down the boundaries that had been taught to us. This is something bell hooks speaks to with so much grace. In All About Love, she writes:

“When we choose to love, we choose to move against fear… against alienation and separation. The choice to love is the choice to connect — to find ourselves in the other.”

That kind of radical love — the kind that connects us rather than divides us — is foundational to Black pride. It teaches us that to embrace ourselves is to open up the possibility of embracing each other. Audre Lorde’s work helped me feel like I didn’t need to apologize for my presence;

“Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”

I finally gave myself permission to care for what mattered to me without guilt. To see softness and pride as weapons against systems that wanted me exhausted, ashamed, and silent.

That’s the root of revolutionary pride. It’s not about loving America blindly. It’s about loving ourselves — and each other — so fiercely that we remake the world in that image.

Yosephina Peters Working On Protest Stencils for BLM, 2020

BLM Protest DTLA, 2020

So, what do we do with our Pride? How do we hold it and utilize it, especially when the world feels too heavy, too fast, too much?

Activating pride doesn’t always mean marching in the streets or standing at podiums. As the late John Lewis urged, we should get into “good trouble, necessary trouble” — but not all of us will find ourselves in heroic moments. And that’s okay. Most of us are just trying to get through the day. The struggle of the American worker, the caretaker, the student, the artist — that struggle is resistance in itself.

Pride begins in conversation. Not always public debates, but quiet, unglamorous talks at dinner tables, in cars, in laundromats. They’re not always easy. In fact, the best ones rarely are. They challenge us, stretch us, expose us — but they also connect us. And when those conversations come from a place of deep love — even when we’re frustrated or afraid — that’s where something new can begin.

You can also write. You can love. You can make art that honors your anger and your joy — that speaks to the complicated love you might feel for this country, or for the people surviving within it. Sometimes, that love looks like grief. Sometimes it looks like dejection, even rage. But expression — the act of releasing — makes room for new imaginings. For different futures.

All these reflections — the truths of our history, the traditions of resistance, the depth of Black and Indigenous pride, the radical practice of self-love — have led me to a different understanding of what American pride can be. And what it must become.

Right now, in 2025, it’s hard to say “I’m American” and feel warmth. The current administration, under Trump’s second term, has made it clearer than ever that democracy was never their goal — control was. Freedom was never meant for everyone — only for the few. We are witnessing open attacks on education, trans rights, reproductive justice, and even the basic ability to protest. And globally, we are watching the brutal genocide in Gaza, with the U.S. continuing to fund and arm the destruction of Palestinian life.

So no, I don’t have pride in that America because that isn’t our America. I don’t have pride in a country that lets corporations own everything and politicians escape accountability while people starve and cities burn. But I do have pride in something else.

I have pride in the people. In the Americans and allies camping out for Gaza on college lawns across the nation. In the mutual aid organizers handing out water bottles during heat waves and unhoused sweeps. In the drag performers, teachers, and parents fighting for queer youth and the right to have rainbows on their wall. I have pride in those who choose love over fear. In those who demand that liberty, justice, and democracy be more than words recited at ceremonies — that they are practiced.

I have pride in shaping an America that still believes in its own stated values — democracy, liberty, equality, justice, and human dignity for all, not just the chosen few.

Pride, to me, is fighting for what you love, even when it hurts. Even when you're scared. Speaking out even if your voice shakes. It's about holding this country accountable to its promises — not to punish it, but to free us to imagine something better. To me, pride is not about allegiance. It’s about action. Pride is the trees sharing resources to ensure the whole forest survives. Pride is tilling the soil. Pride is the fight of the people. Pride is love.

COVER: ANGELA DAVIS BY YOSEPHINA PETERS, 2020Bart’s Books Shopping List:

Nikole Hannah-Jones, The 1619 Project. One World, 2019.Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions, 2015.Patrick Wolfe. Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. Cassell, 1999.Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Beacon Press, 2014.Barbara Ehrenreich, Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America. Henry Holt and Company, 2001.Angela Y Davis, Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement. Haymarket Books, 2016.Angela Davis, “Abolitionist Movements in the 21st Century.” Delivered at the Missouri Theatre, Columbia, Missouri, 24 January 2017.bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions. William Morrow, 2000.Audre Lorde, A Burst of Light: Essays. Firebrand Books, 1988.